After a year of social distancing, I suspect we need to increase the number of words we have for being alone. I think of the old cliché about Eskimoes having many different words for snow – a phenomenon they are especially familiar with. Why, then, are we restricted to only a few words for spending time without other people?

Alone With COVID

As an amateur novelist, ardent student of linguistics, semiotics, and philosophy of language, and occasional stutterer, I am keenly aware of the way that language can drive our thoughts and feelings into certain boxes or dead-ends. And one of those boxes is the association between being alone and sadness. “Alone” connects in our minds to “lonesome,” “lonely,” “loneliness,” “loner.” “Isolation” conjures up images of quarantines and prison cells. “Solitude” has a slightly more positive connotation (think “solitary” or even “Solitaire”), but it still only scratches the surface of the wide network of experiences one can have without other people around.

As an introvert, I have many positive associations with being alone. I can think of the experience of walking through the woods with the pleasant feeling of having only nature for company. I think of the relief of coming home after a long day spent teaching, learning, or working with others, to know that – finally – nobody is watching, judging, or expecting anything from me. I think of the joy and pride of completing a personal project I set for myself. I think of working on my undergraduate thesis in one of the campus computer labs after all classes had let out – there’s a special joy in having a big public space all to oneself, like you’re a spy or a king. There’s the feeling of determination when you go exploring a new city for the first time. The satisfaction in solving a difficult problem without any help. There’s the comfort of working independently, but with a strong safety net and support system, and the exciting anxiousness of doing something secret and dangerous with nobody to help if things go wrong. And plenty more besides.

But I think the idea of being alone has gotten hijacked since the pandemic. It could just be my situation – while many have expressed dismay and frustration with the closure of public places, found themselves with a ton of unstructured time on their hands, and fallen into spirals of anxious self-evasion (along with “doom-scrolling”, Netflix-binging, or the usual cycles of self-flagellating over not using that time wisely), I’ve been busier than ever. When my college classes went online, I found myself scrambling to record lectures, re-organize coursework, field student e-mails, and accommodate myself to the strange and disorienting business of Zoom interactions (which is, to me, all the worst parts of the uncanny valley combined with all the worst parts of normal human interaction – your mileage may vary). Somehow, in the year since campuses started closing, I’ve recorded three full classes’ worth of lectures via podcast, researched and created a course on Christian History, helped found Video Game Academy in its current state, and all while fielding existential horrors and going about being an adult human, just like everyone else. It has been positively exhausting.

And while I am lucky to have kept my job through all this, to have been able to afford rent, to have my wife and my family nearby – I often felt a pang of jealousy when someone online nonchalantly referred to their endless unoccupied time. Maybe I’m lucky, too, that I never had to face the gnawing dread of waking up with nothing to do but see what new horrors the day had in store – that I always had some new project, and relatively little spare time for anxiousness and doubt. I admit that’s possible. But I also think of all the time I would have liked to spend writing, or all the video games I haven’t had the chance to play, or all the books I’d like to re-read. I’d like to think I would have handled that dead time well, though that’s only speculation.

But when I say ‘hijacked’, I mean more than just the way people talk about their isolation as something unpleasant, unnerving, and anxious. I also mean that the pandemic itself has ‘hijacked’ – or ‘transformed’ – isolation into something unfamiliar. The way we actually ‘be’ alone has also changed. There are miles of distance between nestling on the couch to read a book because you’ve decided that this is the best use of your time, despite all the other things in the world clamoring for your attention – and nestling on the same couch, with the same book, because there’s nothing else to do. Or because you are too afraid to watch the news. Or because you’re trying to ignore the fact that a friend, a co-worker, or a family member has fallen sick – and there’s nothing you can do about it. There’s also something very different about the relationships you have with your roommates – be they friends, colleagues, romantic partners, family members, or just casual acquaintances – when you are stuck together with them and forcibly removed from everyone else in your life. Some relationships function best with healthy periods of distance, as I’m sure many husbands, wives, fathers, and mothers know all-too-well after a year of this. Not that they care any less for one another, but that they have been coerced into that caring. For all those people who struggle with isolation in the age of the pandemic, there are other people who chafe at being trapped in close-quarters with the same people, day after day. And the strangest thing of it all is that it’s often the same people who feel isolated and chafed at the same time.

I’ve come to start thinking of this problem (of feeling alone and trapped with others at the same time) in terms of “purity”. When I am alone (in theory) but at the beck and call of my students, or waiting for my wife to arrive home, or working at some task for someone else, I tend to think of that as an “impure” isolation; while having the consolation of knowing that nobody is going to disturb me for hours to come is a more “pure” experience of being alone. Likewise, I imagine that extroverts seek out a social interaction that isn’t limited to the same two or three people in the same mundane and over-familiar circumstances – a more “pure” or “free” engagement than being stuck seeking solace in fraying relationships.

But what this often means, since these “pure” experiences of isolation are becoming more and more rare for me, is that I seek out ways to make myself feel more alone than I actually am. Like the person on the bus wearing headphones or studiously looking out the window, I look for ways to disengage from my unavoidably social circumstances and experience “virtual” isolation. I want to be more alone, in short.

And, strange as it may be to say, video games are really good at this.

Escapism and Isolation

I say “strange” because this doesn’t sound like the usual back-of-the-box feature like realistic AI, high-end graphics, or online multiplayer. If anything, games like to downplay the fact that they are, for the most part, ‘isolating’ experiences – by which I mean that they are usually played alone, absorbing you into the worlds and mechanics, and diverting your attention from other people around you (I have been on both sides of the “trying to get someone’s attention while they are playing a video game” dynamic).

But that doesn’t change the fact that this “absorption” is one of the key reasons why people play video games. “Escapism” is the word we usually use to describe this desire, but a key component of that “escapism” is how we let these richly-designed worlds and engaging gameplay “absorb” us out of our world, responsibilities, and interactions with others. They make us feel like it is OK to ignore the dirty dishes, the unopened e-mails, or the gym membership we promised ourselves we would use. And there are an endless number of techniques used by video game designers to make us feel this way, but the upshot is that many—if not most—games supplant our tedious and frustrating world with one that is exciting, interesting, and which (quite literally) revolves around us.

Sometimes this is very obvious. Horror games like Silent Hill, Dead Space, or (appropriately) Alien: Isolation do a lot of work to make the player feel alone in order to exacerbate the feeling of helplessness, and therefore prime them for tension and scares. That’s how they deliver on the promise of horror.

But I think, too, of all those games that feature large, empty environments for the player to explore and overcome. This was the cornerstone of the Legend of Zelda franchise, and I find it especially fitting that Zelda fans are usually quick to react when the game interferes with that sense of loneliness (as in the case of Navi or Fi). And this extends to virtually every game with an open world (except, possibly, MMOs), whether it’s the sprawling empty wilderness of Fallout or Skyrim, riding across empty American deserts in Red Dead Redemption, sneaking through mansions in Thief or Dishonored, or flying through the stars in Elite: Dangerous or No Man’s Sky.

Go further, and you can include all the games that position you as “the only one” who can save the world, or rescue the princess, or overcome the bad guy. Mario, Sonic, Final Fantasy, Dragon Quest, Doom, Wolfenstein, Half-Life, Assassin’s Creed—even most of the campaign modes in team-multiplayer-focused titles like Call of Duty or Gears of War tend to stress how important it is that YOU complete this task, because YOU ALONE can win the day.

In all of these cases, whether intentionally or unintentionally, these games isolate the player, pull them out of the ‘real’ world, and deliver the experience of being the only person who matters—a more “pure” isolation—at least for a little while.

Now Featuring Oppressive, Isolating Environments!

But as much as I think it was largely an accident of genre or design in the past, I suspect that game designers are increasingly interested in delivering a specific feeling of being alone. Breath of the Wild is the loneliest game in the Zelda franchise since Majora’s Mask. Naughty Dog went from a flagship title about a wise-cracking Indiana-Jones-alike escaping from set-piece explosions to the much more moody and lonely The Last of Us. Indie games like Hollow Knight and Inside delivered on the loneliness promised by forerunners like Limbo. And I imagine that a lot of this renewed interest in loneliness is brought about by the juggernaut success of From Software’s Dark Souls and the “souls-like” genre it inspired. In fact, I suspect that Dark Souls is the quintessential “isolating-game” in the sense I’m describing here. Without steering into outright horror, Dark Souls routinely makes the player feel isolated, through its large, oppressive level design, sparing use of dialogue and NPC’s, and focus on ruthless difficulty.

And this has actually been a hallmark of From Software’s game design for a long time—longer ago than Dark Souls or even Demon’s Souls. Back in the PS1 era, starting in 1994, their flagship title was King’s Field, a game (much like Dark Souls) which focused on navigating traps and powerful enemies in an oppressive, lonely medieval environment. I can’t speak much to the franchise, honestly—I was thoroughly smacked around by the PS2’s King’s Field IV: The Ancient City when I got around to it in the late-2000s, but I remember it being a largely-ignored franchise often held up by other devs for some really smart game design choices that didn’t connect with gamers of the day. (Probably because it was just so difficult…)

What I can speak to, however, is another entry in From Software’s ignored back catalog—barely a blip in the twenty-six year history of this surprisingly storied company. A game that is every bit as oppressive and lonely as the other, more famous games associated with the company, and one that I regard as an overlooked masterpiece of the early 2000s.

What’s more, perhaps we can finally answer the question: “Why does Professor Kozlowski hate Dark Souls so much, yet inevitably ends up writing about it in every essay?”

It’s because I’m still waiting for Lost Kingdoms III to come out.

2001: A Video Game Odyssey

In the summer of 2001 I had just graduated from middle school and was gearing up for my high school career. I had disposable income from graduating eighth grade and I was getting (eventually) a brand-new bedroom in the basement after giving up my room to my aging grandmother. That summer I finally bought a PS1 and my own television (we had been a one-TV household up to this point, and I sold my parents on the idea by arguing that I would only use it to play games), much to the chagrin of the Wal-Mart checkout guy, who kept trying to sell me on getting a PS2 instead. But I was determined to get a Gamecube when it released in November (plus, at this point PS2’s had started spontaneously combusting in living rooms, and that was just the kind of hassle that could jeopardize my newfound independence).

I spent the summer playing Final Fantasy VIII on the PS1, reading my Nintendo Power subscription, and playing Perfect Dark with my friends in the neighborhood. When fall rolled around, I adapted neatly to high school (my mother taught French there and I had been taking high-school math in eighth grade because I was that kid). Which was good, because 9/11 happened barely a week into the school year, and the following months would be filled with the world-shaking craziness of terrorist threats, anthrax letters, and Bush’s “War on Terror”.

But, happily, that’s not what this essay is about. I was only fourteen, after all, and pretty oblivious to the gathering storm of cultural forces that would haunt politics to this day.

Instead, I eagerly pre-ordered my “Gamecube Bundle” from the fledgling Amazon.com using our swanky 56K Internet connection. I scored Luigi’s Mansion and Star Wars: Rogue Leader (two very solid release titles IMHO), followed quickly by Super Smash Bros. Melee and Pikmin in December (because Nintendo knows how to release a new console right).

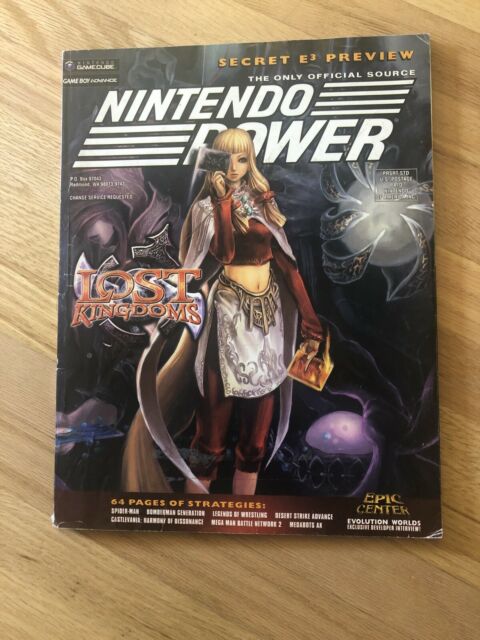

But as the new year of 2002 wore on, I found myself in a release slump. I had money to burn, but no hot new Gamecube games were on the horizon until Super Mario Sunshine in the summer and Metroid Prime that fall. So I took a chance and bought a middlingly-reviewed third-party title called Lost Kingdoms.

And while I would ultimately trade in Luigi’s Mansion, Pikmin, and Super Mario Sunshine for other games, Lost Kingdoms never left my collection.

How Do I Love Thee? Let Me Count the Ways.

I’m honestly a bit overwhelmed by all I have to say about this game. My thoughts about this forgotten franchise are many, complicated, and not entirely clear. I want to talk about that same oppressive, isolating atmosphere that From Software was well on its way to perfecting at this point in their career. I want to talk about the fact that I, a fourteen-year-old teenage boy, was somehow inexplicably drawn to this game about princesses fighting monsters with magic cards, despite all the usual teenage-boy-angst about masculinity and male/female dynamics. I want to talk about the fact that this game isn’t necessarily “good”, but how all its choices are deliberate, focused, and effective all the same. I want to talk about the sequel and how the gameplay evolved—improving some things while losing some of what made the original so great. And I want to talk about why it somehow did not catch on, even after so many games from that time have been dug up and re-examined as classics or even masterpieces. I want to write my little love letter, in the hopes of making my contribution to the thirty(?)-year-cycle of nostalgia, and maybe…maybe winning us the sequel that never happened. (A pipe dream, no doubt.)

But I guess we ought to start with the basics.

In Lost Kingdoms you play as Katia, princess of Argwyll. You sit on the throne while your father, the King, ventures abroad to investigate a mysterious black fog which threatens the countryside. The game begins with a foot soldier bursting into the throne room—the fog lies at the threshold and the castle is infested with monsters! You must take up the mysterious and sacred runestone and flee the castle, following your father, to unravel the mystery of the fog’s origins and fight back the tide of oblivion.

To do this, you must use Lost Kingdoms’ most unique feature: the runestone allows you to use magic cards, each of which is played in real time, for a wide variety of effects: ranging from weapon cards (which can be employed to do quick damage multiple times, like swinging a sword or stabbing with a spear), to summon cards (which can heal, do massive damage in a specific arc or range, or any number of other effects), to independent cards (which appear on the battlefield and independently engage, harass, or affect enemy monsters). Your “hand” of four cards are mapped to the four primary buttons on the controller; as you use cards, new cards are drawn to their places from your deck of thirty cards.

What’s more, each of the cards corresponds to the game’s enemies. Beat a skeleton in the first level and you have a chance of drawing the skeleton card at the end of the level. Weaken a monster sufficiently and you can capture it by throwing one of your card options at it directly. The way the monster behaves as an enemy does not necessarily correspond to the way the card will behave when played, but it is usually comparable, corresponding to the monster’s attacks or behavior on the field. Furthermore, each of your cards gain experience individually, and can be duplicated or even transformed into other cards with sufficient experience.

So think Pokemon collection mechanics crossed with Quest 64 or Tales of Symphonia real-time combat instances and you’ve got a pretty good idea how the gameplay works. But where Pokemon typically limits you to one (or, in years to come, two and three) combatants at a time, Lost Kingdoms offers considerably more freedom. In a fight, you’ll typically be running around the field avoiding attacks from enemies, looking for an opening to strike with weapon or summon cards, or buying time for your independent monsters to chase your enemies around the battlefield. But there is a good bit more depth that even this description suggests. Some independent monsters instead draw attacks from enemies, or weaken certain elemental attacks, or increase speed or attack, or lay dormant on the battlefield as a trap for enemies who come too close. Weapon and summon cards vary wildly across variables like amount of damage, range, frequency of attack, status effects, and so on, requiring you to position yourself carefully before attacking. Furthermore, you pay for cards by spending magic crystals, which have a tight cap, forcing you to get close to pick up dropped crystals from damaged enemies during prolonged battles.

So on the tactical level there is this constant push-pull between avoiding attacks and collecting crystals/doing damage. On the strategic level you are trying to prioritize experience for cards you want to transform while also building your deck around the level’s elemental weaknesses. Like any good card game, there are a lot of variables to consider, and like any good action game, you have to learn enemy movements and attack patterns, while adapting to opportunities and setbacks.

And let me stress for a moment the sheer ambitiousness of these choices. In April 2002, we were still some months out from Pokemon Ruby/Sapphire, which would up the Pokemon roster to just under 400, though the animations were still rudimentary and the combat turn-based. Pikmin was comfortable rendering many more on-screen characters, but their animations, while more crisp, weren’t nearly as diverse. We’re talking about a hundred unique attacks and moves, paired with a hundred uniquely-animated monsters, all animated, balanced, and interacting with one another in real time. What’s more, each card appears in the UI with a design distinct enough to be recognized at a glance in your four-card-hand without words, enumeration, or any other kind of hint to the player what the card does, since you typically learn how the cards work solely through trial-and-error. I’m not sure anything close has been done since—besides Lost Kingdoms II upping the card count to roughly 225 and doing it all without the limitations of instanced combat encounters—one year later.

The Subjectivity Caveat

Some games appeal to a massive audience because they offer something that everybody wants. Zelda promises to let you be a hero and save Hyrule by solving puzzles and beating up monsters, and people have been coming back to that well for generations now. Call of Duty offers a wide variety of ways to shoot cool guns at your friends without actually hurting each other, and it has been going strong for over a decade. Fortnite lets you dress up your avatar and hang out with your friends while occasionally completing quests and killing each other off, and it’s has earned lasting popularity as a result.

But sometimes you find a game that appeals directly to YOU. It fulfills some desire of yours in a way that you specifically understand and appreciate.

To give an example, I absolutely ADORED Outer Wilds. I love science-fiction, hiking in the woods, puzzle-solving, abstract physics and philosophy, and exploring virtual worlds, and Outer Wilds somehow ticked every single one of those boxes for me.

But when one of my friends asked if he should get it, I told him that he wouldn’t enjoy it. He was initially a bit miffed by my response, but I told him that we played games for very different reasons. I love exploration for the sake of exploration; he likes many of the same games because he enjoys the accomplishment of fulfilling objectives, following storylines, and overcoming obstacles. Outer Wilds has virtually none of that. There is zero hand-holding, zero guidance, zero clear goals.

Outer Wilds spoke to me in my own language, in short. It was my perfect game, but not everyone would have the same reaction.

Likewise Lost Kingdoms ticks a lot of my boxes. It has complex tactical and strategic depth with a wide variety of options and abilities that you unlock gradually as you get more familiar with the game and its challenges. It takes place in a haunting, lonely world where most of the other characters are dead, missing, or just plain absent—allowing me to feel very much alone and in control of the situation. Its fantasy is high and arch, more interested in realizing archetypes than finagling detailed lore. It’s everything I loved about Pokemon paired with everything I loved about The Neverending Story, along with quite a bit that I never thought I needed—or wanted—from a game before.

But the question I find myself asking is: why don’t more people see the appeal? Is this a game just for me, or a game I specifically appreciated? Why did this fail, but Dark Souls succeed?

To answer this question, I want to seriously dissect this game. More than just a cursory analysis as I’ve done in the past. Because the strangest thing about my deep love for this game is that I find that I enjoy precisely the same things that I suspect most people would critique. Its failings and successes are somehow bound up in one another, making it a knotted puzzle for any critic to try to tease out. But that’s all the more reason to try, and see what we find out about myself, games, and popularity in the process. Is my love for this game, itself, something isolated; or is this a case of an overlooked gem waiting to be re-discovered?

Criticism #1: Lost Kingdoms is too Short

Lost Kingdoms clocks in at roughly ten hours to complete. My best record is around nine; when I’m being especially thorough (or clumsy), it takes about eleven.

Note that I said “complete” – by which I mean not just beating the game, ignoring side quests, but completing every level and collecting every card.

Virtually every negative review I’ve seen on the game lists this as its first complaint, so it’s worth considering. But I honestly cannot wrap my brain around this. Yes, the average Pokemon game takes twenty to forty hours to complete, and I’ll typically sink over one hundred hours into a new generation as I complete additional quests, capture rare Pokemon, and bring old-gen favorites to the new game. Likewise, any Final Fantasy game will take thirty hours or more to complete.

But ten hours is also pretty standard for an FPS, or for a platformer like Mario, or an action game like God of War or Devil May Cry, or even some of the Zelda entries. And as much as I’ve compared the collection aspect of the game to Pokemon, you could just as easily make the case that the gameplay has more similarity to action games than RPGs. So, by that logic, it should be held to the same standard, which it reaches admirably.

But what’s more, I agreed with this critique the first time I played the game. I also thought it was too short. Which is just another way of saying: I wanted more.

So, directly after finishing the game for the first time, I played it through, start-to-finish, again.

And I have played it through, start-to-finish, close to a dozen times since, I imagine.

Because ten hours is absolutely the perfect length for this game.

Seriously, I cannot comprehend how it would be improved.

In the forty hours you spend playing the newest Pokemon game, you will spend a solid ten-to-twenty doing crap you don’t want to do. You will fight an endless succession of random Pokemon you don’t care about while looking for the one super-rare Pokemon you want to catch. You will spend hours reading wooden dialogue, going through the same tutorials, backtracking through areas you’ve already explored. You will grind, and grind, and grind levels and experience.

And I say this as a deep lover of the Pokemon games, knowing full well that there is something cathartic and relaxing about a lot of this. I suspect that Pokemon’s slow pace is part of its success. It is a very player-friendly, low-stakes game, largely so anyone can pick up the game and play it, no matter how young they are, or how few (or many) video games (or Pokemon games) they’ve played in the past.

But that doesn’t stop me from spending a decent proportion of my time playing Pokemon speeding through dialogue, ignoring cutscenes, wasting time waiting to get to the good part.

Lost Kingdoms is almost all good part. Once you have completed a level, that level locks you out (until the very end of the game). It forces you to constantly push forward, explore new areas, face unfamiliar risks and challenges. You are never permitted to grind, unless that grinding happens organically (your cards retain experience when you die in a level). What’s more, the game is so precisely balanced that you can, by beating every level this one time, successfully obtain every card in the game—if you use your time and experience wisely and prioritize training a wide variety of cards.

Pokemon is a fifteen hour game with twenty-five hours of filler. Lost Kingdoms is a ten hour game with zero filler. And if Lost Kingdoms more efficiently provides the same high of conquest, the same fulfillment of collection, it is the superior game.

The Long and the Short of it

But I realize that I’m being fairly flippant about a surprisingly heated issue among game critics. And especially in 2002, game length was a fairly important subject for debate. This was before the indie revolution, after all, when all games were $50 (or $60, I honestly can’t remember if that had happened yet) AAA releases. What’s more, this is right on the heels of the PS1/N64 console war, where much of the debate circulated around the N64’s superior processing power versus the PS1’s CD-based games (which could store significantly more data and, consequently, longer games).

The debate can probably be best characterized by contrasting two of the most beloved games of the generation (and frequent contenders for “Best Game of All Time” in video game discourse): Final Fantasy VII and The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time. Ocarina had full 3D environments and exploited that to the utmost with manual aiming and puzzles that required use of the vertical and horizontal axes of play, where FFVII cheated most of its environments with 2D backdrops for rough 3D characters. Ocarina’s gameplay was in real time, with very few cutscenes, all of which used in-game mechanics, unlike FFVII’s turn-based JRPG battle system, and frequent use pre-rendered cutscenes for both storytelling and combat. But Ocarina was only twenty hours long to FFVII’s whopping sixty-to-seventy hour campaign over three discs, and FFVII’s justly-lauded story seemed (at the time) much more “mature” and “artistic” to Ocarina’s sparse approach.

I think part of the reason critics got so hung up on game length in the early ‘aughts was a holdover from the PS1 v. N64 divide: die-hard PS1 fans clung to the value of long, involved storytelling to retroactively justify the virtues of the console. And that got bound up with Nintendo’s image as a “kiddie” console, not suitable for “serious” games. So it became fairly commonplace to criticize games (and RPGs especially) for their brief length when compared to “grown-up” games with huge, sprawling campaigns.

But on another level, I think part of the motivation, too, has to do with the cost. Games have always been expensive, and an easy way to justify that expense is with length. We math-and-science video game nerds looked for a simple quantitative way to justify the quality of our games, and a pretty easy solution was to calculate worth according to how much time we spent with the game. We thought in terms of “return for investment” – paying $50 for a game that took me fifty hours to beat meant that I spent about $1 per hour. Whereas Lost Kingdoms, which took only ten hours to beat, meant that I spent about $5 per hour.

But, as I’ve argued elsewhere, that assumes that time is of no value to the player, and leads to some pretty dodgy conclusions (by that logic, Cookie Clicker is the best game I’ve ever played, seeing as it was free and took up a lot of my time). Super Bunnyhop has done some excellent work on this subject, pushing back against the usual assumptions surrounding the debate, and coming to some interesting conclusions.

When I say that Lost Kingdoms is the perfect length, I mean that it does not waste any of my time. I mean that I am happy to revisit it, over and over again, because it does not represent an inordinate commitment or undertaking. I mean that a shorter game would not be as satisfying, but a longer game wouldn’t be as easy to pick up and put down. I can start a run through Lost Kingdoms without it seriously delaying other undertakings or projects. And, what’s more, the fifteen-minute discrete levels are also perfectly-suited to fit into a busy schedule.

But I think the question: “Is it worth $50?” is a valid one. Should I expect more game for my money? Much as I may belittle the straw man version of this question, I respect the thinking. But, in my case, having replayed the game a dozen times for a total well over 120 hours, the answer is an obvious yes. I am happy with what I got. But that, of course, just brings us back to the qualitative questions: “Is it good?”

Criticism #2: Lost Kingdoms Lacks Polish

If I found the first critique straightforwardly superficial and unhelpfully objective, I find this one convolutedly vague and dubiously subjective. And yet it comes up every bit as frequently as the first in what few discussions I can find of Lost Kingdoms.

On some level, though, I understand the criticism. By “polish” we usually refer to how the game (or other work of art) seems “finished” or controlled. A polished game looks clean at every shot, lacks bugs or glitches, feels tight and responsive, and rarely (if ever) reveals its technical limitations. When the camera in Super Mario 64 gets stuck behind a rock, that betrays a lack of polish. When Altair’s flowing assassin robes clip through his feet in the running animation, that’s lack of polish. When your avatar in Skyrim snaps unrealistically to the mining animation, that’s lack of polish. And when the camera in Lost Kingdoms cuts through the walls of the level to show the summoning animation, that’s lack of polish.

But polish exists in a sort of permanent tension with ambition, and, as I’ve stressed, Lost Kingdoms is all ambition. With one hundred cards, one hundred monsters, all uniquely animated and with distinct behaviors, the number of edge cases are frankly astronomical. Debugging the game must have been an absolute nightmare, much more than other action games, where the avatar has a fairly limited set of attacks and movements and the monster AI can focus exclusively on the player character. Contrast this with the precise, studiously controlled environments of Dark Souls and the handful of different possible player movements and actions, and the difference is night and day. Much more energy could be devoted to the few edge cases than in Lost Kingdoms.

The solutions made by the game seem pretty obvious and general. Lost Kingdoms’ camera remains fixed at one of four positions, diagonally looking down at the level, much like the camera positioning in an isometric RPG like Diablo or Torchlight. You can zoom in and out at three different magnifications, but that’s the sum total of your camera freedom (LKII frees up the camera for a more traditional, over-the-shoulder 3rd-person view, but I’m not sure it works any better, for reasons we’ll discuss). What’s more, when you enter a combat instance (the only time you can play cards), the background and the rest of the level drop away, leaving you on a grid-like isometric square in a blue void. This usually (but not always) drops away barriers like walls and obstacles that would obscure your vision.

Ninety-nine percent of the time, this works. The rare time I’ve lost track of my player avatar, it’s because of the frenetic busy-ness of the combat, and has nothing to do with camera positioning or level design.

But then there are the summon monsters. The weapon and independent monsters all happen in real time on the battlefield, and the isometric-ish camera positioning takes it all in stride. But the summon monsters have an RPG-style animation preceding their attack, and the camera snaps into a pre-ordained position to more dramatically herald the monster’s appearance. And, in doing so, the camera sometimes snaps behind level geometry, or the summoned monster ends up positioned impossibly bisected by a wall, or any number of weird scenarios that occur when the player avatar is suddenly replaced by something ten times as large, like a kraken, dragon, or hydra. You could do away with the dramatic summoning animation and avoid a lot of these problems, but at the expense of the game’s diversity and pacing (summoning monsters provides a distinct break in the frenetic action of combat), not to mention the catharsis of watching a huge freaking dragon climb up out of the ground to breathe death on your enemies. Summons are dramatic here, just as in Final Fantasy, and I appreciate the attempt to integrate the summoned creature as a spatial entity in real time—much as the summons may be less dramatic than Bahamut or KotR, there’s a greater heft to their actions when you see them springing onto the actual battlefield instead of appearing through some snazzy pre-rendered cutscene. And there’s something wonderfully satisfying about getting the timing and positioning just right, laying waste to four enemies simultaneously with the Red Dragon’s breath attack, or the Necromancer’s shield.

Now the animations themselves do vary a bit in quality as well. Some are especially dramatic, like the Giant Crab slicing the card that summons it in two, or the Vampire’s foppish, contemplative chin grab before arbitrarily killing random monsters on the field. Others, like the Birdman’s over-shadowy spear thrust, are less impressive. Certainly another pass by the animators would have been well warranted, and some of them were fixed by the sequel (others were even worse – poor Sand Worm). I see the critique, but I also find it unfair. Final Fantasy X, released the year before, had a mere eight summoned monsters, all using pre-rendered cutscenes and cherry-picked battlefield environments. Naturally, it was much more polished; it was much less ambitious. LK had over thirty summoned monsters, each of which could appear at any point on any battlefield; I am more than willing to overlook a little polish as a consequence.

Polish vs. Ambition

Most of the other “polish” critiques fall into similar categories. The AI for the independent monsters is occasionally spotty. Some cards are disproportionately more powerful than others. Some of the levels seem more carefully designed than others. Some elements of the UI can be difficult to read or understand (especially on small TVs). And while I agree with some of these critiques, and can agree that adding an extra month or three to the game could have helped its release considerably, I keep finding myself at the same conclusion.

I don’t care.

There are a dozen Final Fantasy games, a dozen Legend of Zelda games, Mario games out the yin-yang, and souls-likes pouring onto digital storefronts in droves. Enough that some releases are utterly forgotten amid the more standout entries in a series or genre. When I traded in Super Mario Sunshine, it was because I thought Super Mario 64 and Super Mario Galaxy were more than sufficient to meet my 3D Mario platforming needs. Final Fantasy X met with positively unreal praise when it released in 2001, but I consider it a real step backwards mechanically from the likes of FFVII and FFVIII, and a fairly forgettable entry in 2021.

There are two Lost Kingdoms games. That’s it. And I don’t have high hopes for a third. Those mechanics died on the vine. And now that the indie market has been flooded with deckbuilding Slay-the-Spire alikes, you would think somebody would be mining that old vein—but they are not. The closest I’ve seen is probably Hand of Fate, which I really enjoyed, but which was also far less ambitious.

And I suspect I know why those mechanics did not catch on. I suspect it is specifically because there is no possible way to polish them. An action-RPG with that many variables will, necessarily, be unpolished. It will never look as good as something meticulously controlled, with a much more limited moveset and a player character with only a few animated permutations. And, what’s worse, polish sells. Final Fantasy X succeeded because it was one of the most polished games ever released in 2001. It looked great, in part because it ditched all those ugly labor-intensive mechanics like a world map, real-time combat, unique and flexible character builds – all hallmarks of the franchise up until that point. With the possible exception of Blitzball and the world design, it was one of the safest entries in the franchise, and remains one of the most highly-regarded and profitable.

But I will take the ambitious mess over the polished pablum every time. I will take Skyward Sword’s weirdo time-jumping puzzles, high-flying world navigation, and Fi’s incessant tutorializing over Twilight Princess’ return to Ocarina’s form. I will take FFVIII’s spreadsheet Junction system, arch teenage romance, and quasi-academic mercenaries over FFIX’s nostalgia for earlier games and FFX’s swanky graphics and quality-of-life improvements.

And I will take Lost Kingdoms’ wild, unpredictable, tactical, messy combat over God of War II’s taut, polished execution (six years later), or Pokemon Colosseum’s tightly-controlled turn-based combat scenarios (two years later), or even most real-time combat systems today. And if polish is the price I have to pay to get that experience again, I will pay it gladly.

But apparently I am alone in that opinion.

Criticism #3: Lost Kingdoms is Bland

I prefer science-fiction to fantasy.

I want to state that out the outset of this section, because I suspect it is more telling than it first appears. It seems to suggest a pure subjective preference: I like my characters wielding ray guns rather than crossbows, lightsabers over swords. And these days, with the two genres as blended as they are, it is sometimes hard to see any greater distinction than these superficial trappings.

But there is something fundamentally different about the two genres—even something diametrically opposite. Fantasy (at least as we have it now) is, essentially, about the past. Science-fiction is about the future. Fantasy revels in its histories; Science-Fiction revels in its ideas.

What I’m talking about here is lore. And that I don’t give two farts about lore.

Don’t get me wrong—good, well-written lore is involving and interesting. I’ve read The Silmarillion a good half-dozen times and it may have usurped my love for The Lord of the Rings. But I love it as its own set of stories and mythology, as this utterly unique creation of an utterly unique writer.

But when a game like Dragon Age: Origins or Final Fantasy XIII gets on a lore-jag, I tune out. When a fantasy writer starts getting more caught up in backstory than character development, I look for a new book to read. And even when I was DM’ing a Pathfinder campaign, I had no interest in the world-lore at my fingertips, preferring to create my setting from scratch.

I’ve since learned that this is pretty abnormal among fantasy fans. Nerd-dom takes great pleasure in dissecting the fine details of continuity and lore among their favorite properties. They write detailed backstories to be gradually revealed over the course of a D&D campaign. Secrets and twists are their bread-and-butter.

I’ll pass on all of it. Maybe one day I’ll make my case for this perspective; at any rate, it won’t be helpful here. Suffice it to say that my favorite fantasy is mostly lore-less, or that lore exists purely as backdrop to the ongoing story. (In no particular order, my favorite non-Tolkien fantasy novels are: The Last Unicorn, Sabriel, The Neverending Story, So You Want to Be a Wizard, and Taran Wanderer – all of which are very light on lore, but heavy on metaphysical import.)

So when people criticize Lost Kingdoms for being “bland” or “generic”, I make my quizzical face, and find myself wondering if they mean what they say.

But let’s consider the three most likely possibilities for what makes Lost Kingdoms generic:

Criticism #3.1: The Creatures of Lost Kingdoms are Bland

In my experience, when somebody makes a sweeping generalization about a video game, movie, novel, or any other work of art, the most likely aspect of that work they are talking about is the elements. They are the qualities most immediately apparent and recognizable to the audience and yet least easy to discuss. You turn on the black-and-white filter and heavy shadows and you’ll convince most people they are watching noir, even if none of the usual themes are present. Start a story with somebody fighting a mystical creature with a sword, and people will think it’s fantasy, even if the story beats seem much more geared to historical fiction. (Looking at you, fans of Mr. R. R. Martin)

Lost Kingdoms is, superficially, generic. The monsters (and cards) can typically be found in your average D&D Monster Manual. You’ve got skeletons, dragons, lizard-men, mummies, carnivorous plants, vampires, golems, phoenixes, necromancers, demons, mandragora, cockatrices, fairies, octopus-monsters, krakens, sphinxes—you name it. It’s a giant mish-mash of monsters from a pretty wide variety of folklore traditions. Nor is there any effort to explain the diversity of these monsters. The only hint you receive is that the monsters were created by the gods of the world (we’ll get to those momentarily), and that’s why they can be controlled with the runestone.

Now I’m not especially bothered by haphazard monster inclusion. Much as I appreciate when the monsters are specifically geared to the theme of a game (like the monsters in Silent Hill 2, the album-cover enemies of Brutal Legend, or how the new Pokemon in recent generations are geared to the region where they are found), it is not a deal-breaker when they are not. Final Fantasy has had a hodge-podge of generic monsters for decades and nobody batted an eye. World of Warcraft has somehow gotten away with pandas, gnomes, orcs, dwarves, elves, and demons all co-existing, but they apparently get a pass by performing backflips in the lore, and by using an art style distinct enough to be instantly recognizable.

But from where I’m sitting, cribbing off Tolkien doesn’t win you points. Just because he felt comfortable mixing and matching elements from Anglo-Saxon, Celtic, and Germanic folklore doesn’t give you a pass for doing the same. Nor do you win points for elaborate in-text justification. Either do your homework, or don’t. And if you don’t, it’s best not to criticize others for not doing theirs.

Lost Kingdoms sits squarely in the “didn’t do their homework” category, but doesn’t put on airs about it. And I’m cool with that. Just as I’m cool with anyone working in the Narnia/Fantastica school of fantasy where anything goes because these realms are the manifested dreams, nightmares, and imaginations of human beings. And, though it may be mere head-canon, I tend to think that’s where Lost Kingdoms’ head is at, too. It’s not well-explained (again, LK isn’t interested in lore), but if you combine the suggestion that the monsters were made by the gods with the observation that the monsters spread with the mysterious black fog (itself the product of Helena wielding her runestone and crossing the continental boundary into Argwyll), you reach the implicit suggestion that these monsters are, then, the product of a will to destroy (or create). (The black dragon in LKII makes this pretty explicit when he explains that he serves the God of Destruction.) Helena, then, is literally wielding the destructive nightmares of the people she is terrorizing to achieve her ends. And that is justification enough for me, especially when the monsters are geared to their environments (the Necromancer appears in the graveyard; the evil Enchanter primarily summons skeletons; Efreet primarily appear in the fire realm, etc.).

Criticism #3.2: The Style of Lost Kingdoms is Bland

But this brings us to the next possible criticism: that the design or style of the monsters in Lost Kingdoms is bland. And this is obviously very subjective. But what I will stress is that the monster design is consistent. Monster designs are all, even among the less daunting monsters, threatening and dangerous. Lots of sharp edges, spindly legs, and articulated bones. The red dragon featured on the cover is rendered in-game as all horns, teeth, claws, and spikes. Even the monsters who agree to help you, or who heal you mechanically, tend to be alien and hostile. The game’s lighting tends to be bleak and emphasize the shadows of these figures, which sometimes makes the animations come off a bit drab, but which more often emphasizes the oppressive dark loneliness of the world.

That isolating quality is pervasive throughout the levels of Lost Kingdoms, and a clear precursor to those priorities in the Dark Souls games as well. The few times you encounter NPCs, they are either dead, dying, or hunched over, exhausted from fighting. Most are in heavy armor that utterly obscures their humanity. The levels are, for the most part, universally dark and claustrophobic (at least once you get past the tutorial level on an open green field). Even brightly-lit areas like the desert are obscured by dust, fog, or haze. Interior areas are a bit different, as the camera angle forces this strange effect of the building suspended in an empty void of some kind, but I’ve also found it weirdly effective at communicating this alien, isolating quality all the more.

This is what I mean about the good and bad being inextricable from one another. On the one hand, the environments have this uncanny, unreal quality about them, like the long hallways suspended in a void, the pervasive mist covering the forest, or the discordant, Lovecraftian castle in the final level. But where some might find this uncanny unreality off-putting, I find the effect powerful, and consistent with many of the choices in the game, as we’ll discuss later.

Suffice it to say that this style is not bland: it’s deliberate, consistent, and calculated, both to contribute to the dark, hostile, other-worldly tone, and also to the overarching themes of dehumanization and instrumentality.

Criticism #3.3: The Story of Lost Kingdoms is Bland

This is where I suspect the lore vs. story distinction really needs to be emphasized. Lost Kingdoms offers very little in the way of lore. The one lore-exposition dump we get, in the cathedral library, tells a pretty straightforward story:

Once there were three gods: the god of destruction, the god of creation, and the god of harmony. Destruction and creation warred endlessly, summoning and creating monsters and controlling people to do their will. Eventually their war consumed nearly all the world, at which point the people, with the help of the god of harmony, sealed the two gods away and bound them each with five runestones on separate halves of the continent. To prevent another war, the god of harmony split the continent in two, fencing the warring gods from one another, and separated the runestones, each to its own kingdom, with the understanding that they would be protected and kept separate, because only joining them together could possibly free the imprisoned gods.

But, as we learn through the course of the game, the evil Enchanter collected the five runestones from the opposite side of the continent, freed, and enslaved the god of destruction in the hope of wielding ultimate power. Helena, the princess of the far side of the world, in a desperate attempt to save her kingdom from the Enchanter, broke through the divide in order to collect the five runestones of Argwyll and match the Enchanter’s power.

The black fog, then, is the result of Helena’s invasion into Argwyll. When the game begins, Helena has collected the first of Argwyll’s runestones, and seeks to take Katia’s runestone as her second. She is the threat to the castle that you must flee in the first level of the game. And this is why the king, Katia’s father, has left: he is trying to unite the runestones before Helena can get them, so they can fight Helena off and protect their homeland.

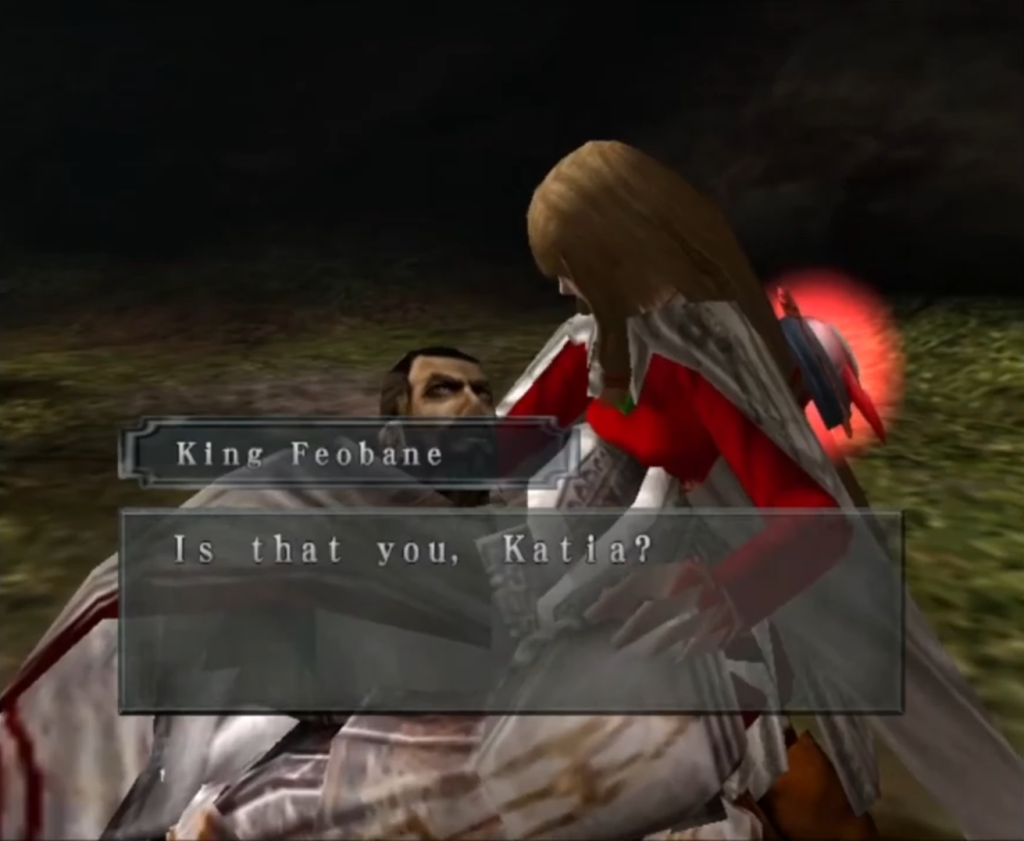

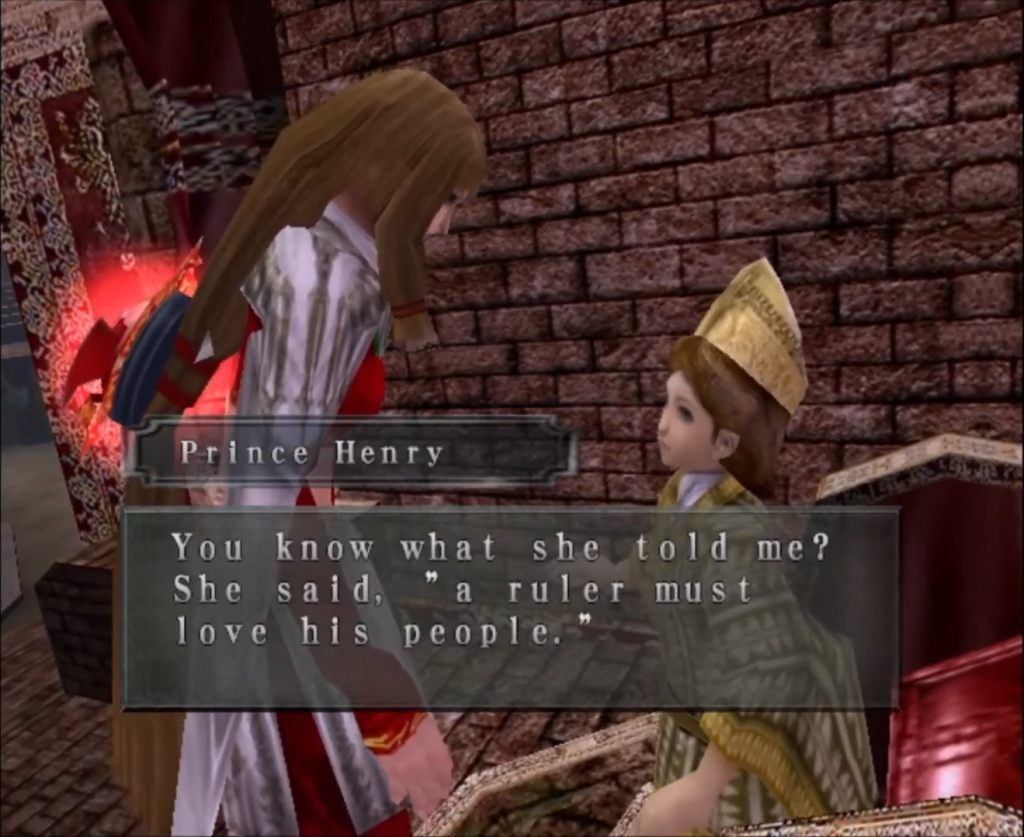

The actual story of the game follows Katia as she unwittingly enters this drama. She flees the castle with her runestone only to encounter the mysterious old woman, Gurd, who teaches her how to use her runestone and directs her to follow her father through the other kingdoms of Argwyll. But where the King failed to persuade the other kings to part with their runestones, Katia succeeds. She wins one runestone by running off Helena as she attacks one castle, wins her third by tracking down the thief who stole it from the Kendarie. She finally catches up with her father on the site of an ancient battle, only to discover that he has been mortally wounded by Helena’s forces. But Katia has no time to grieve. She presses on, beating Helena to the fourth runestone. But Helena issues a challenge: Katia can only have the fifth and final runestone of Argwyll if she manages to defeat Helena at the Sacred Battle Arena. Katia defeats her, only to learn that Helena, too, only wished to protect her homeland from the Enchanter and the god of destruction. Had circumstances been different, they would have been allies, not enemies. Katia swears to fulfill Helena’s mission, and seeks out the god of creation in order to breach the barrier and fight the Enchanter. In the final battle she navigates through the Enchanter’s fortress, confronts him, and defeats him, freeing the god of destruction from his clutches. In a last-ditch effort, Katia must overcome the god of destruction itself and free the world from its power.

…

I don’t know what is meant by a “bland” story—though this is very much the language used by several of the critics—but I can’t imagine this is it. This has everything I want in a story—hidden identities and loyalties, reversals, surprises, unexpected difficulties and obstacles, tragedy, and Katia’s (and the player’s) own personal growth as a character and warrior. Maybe the “god of destruction/god of creation” bit seems a bit abstract, but even they are represented with aims, desires, and plans—more so than your average JRPG final boss/god-surrogate, anyway. Katia’s brief encounter with her father, as well as Helena’s revelation, are both heartbreaking moments of sudden reversal. And the insinuation that Gurd is, in some way, the god of harmony, is a nice tidbit as well.

But the problem is that the game drastically undersells all of this. There are no big dramatic cutscenes, no swelling music, no sudden lighting shifts. Both Katia’s father and Helena die on some of the best-lit settings in the game, as opposed to the rainy graveyards and demolished towns of levels past. The King has the decency to die on an ancient battlefield, surrounded by broken pennants and the bodies of his guards, but the camera’s distance from the action minimizes our empathy with Katia.

The story isn’t bland; the cues just aren’t there to emphasize the beats. If you read the text, understand what is going on, and think through the implications, there’s a rich narrative here—but the presentation doesn’t use any of the cinematic or gameplay cues we’ve come to expect from our video games. It’s all very subtle, very understated, even distant.

That, I think, is the root criticism underlying the suggestion that the game is “bland.” It’s not that any of this is uninteresting, it’s that the tone is distant.

Criticism #3.4: The Tone of Lost Kingdoms is Distant

Tone is so much of what we experience about art. It is the first and most obvious thing we encounter, recognize, and identify with. A strong tone can cover up a lackluster story (as is often the case in the MCU), disguise insufficient character development (as in the DCEU), or make something insubstantial seem smart and insightful (I’ll let you come to your own conclusions on that one…). It’s the first thing we connect to, and we connect to it deeply. Yet we are often at a loss to describe or explain it, since it relates so closely to our feelings, and to our subjective experience. Instead we are usually left floundering: “it feels…right” we begin, casting about for words to describe what we liked, or “it feels…wrong” to describe what we did not like.

But tone is just one tool in the artist’s box, and while a good artist controls tone and uses it to buttress what they are communicating, great artists can use tone to create discord between the text and the subtext, like the triumphant swelling music underlying despicable actions in Nightcrawler, or how The Wolf of Wall Street never drops its light-hearted, breezy pace, no matter how awful Jordan Belfort is to his clients, his wife, or himself (since, you know, society never punished him seriously, either).

In video games, there are a lot of elements that contribute to tone. Is the gameplay fast or slow? Are the animations dynamic or sedated? What is the music doing? Where is the camera situated? How much power does the player wield? How bright are the locations?

In Lost Kingdoms, the answer is almost always the same: distant.

The character animations are slow, regular, almost inhuman (even the monsters move ponderously, for the most part, communicating weight and deliberation). Though the gameplay is fast-paced, it is punctuated by pauses when the character plays a card. The music is soft, slow, rarely more than ambience. The locations are either dark or obscured. And that camera is always, always distant.

Some of this may be due to production values, technical limitations, and other uncontrollable factors of the game’s design. Animating faces in 2002 on the Gamecube’s limited hardware was an expensive and difficult proposition, which is why Nintendo’s more expressive characters typically got a cartoon-y makeover in the Gamecube generation (like cel-shaded Link in Wind Waker).

But Lost Kingdoms aspired to something approaching “fantastic realism”, if that makes any sense. The human characters were meant to have human proportions; the monsters were meant to be shadowy, threatening, but also have heft and weight. The term “dark fantasy” gets thrown around a lot, so I’m deliberately avoiding it, but it would seem to apply here. Katia’s world is threatening, oppressive, real in its danger and isolation. And so the monsters have clearly-articulated teeth, claws, weapons, stingers. Their attacks look powerful and threatening. But they lack expressive eyes or faces, because the realistic dimensions make that level of expression difficult, if not impossible.

And Katia—well, Katia warrants a whole section to herself.

Anatomy of a Female Silent Protagonist

Katia is a very interesting protagonist in the history of video games.

First, she is a woman. And in 2002, this was a pretty rare thing in and of itself.

But, second, she doesn’t fit any of the usual leading-women-in-video-games archetypes. She doesn’t hide her femininity like Samus Aran. Nor does she flaunt her sexuality like Lara Croft. She isn’t hyper-athletic like Chun Li.

And this is actually pointed out in-game. Gurd asks, right there in the first level: “I don’t suppose you have some burly brother stashed away somewhere?”

But more than that, everything about Katia is out-of-place with the rest of the world. She wears this strange white cape, resembling angel wings, and bright red clothes (matching her glowing red runestone) in the midst of a world drab and washed-out of color. She is pristine, shining, even regal in the midst of so much suffering and hopelessness.

Likewise, Katia’s face is rarely expressive, but that lends her as much as it takes away. Katia always retains her regal dignity. Her face is frozen into a distant gaze. Even her weeping for her father is restrained; she still has work to do, after all. She doesn’t roll or dodge out of the way of attacks. She walks, briskly, wherever she goes, only slowing when hurt, at which point she limps (because the pain is real). Her pure-white cape is never dirtied, even when she stomps through a river. Her runestone glows without fail through the darkness, helping her avatar to stand out through the fog of the levels and the fuss of battle. Some of this may be production value (it’s tough to animate faces, or give her a Dark Souls dodge-roll), but the consistency of tone leads me to think otherwise. Katia is meant to be distant, regal, in control (even when she is not). That’s part of her training, after all. Never show weakness. Never let them see you bleed.

But even more than that, Katia is regal—distant—even in combat. She doesn’t throw punches like an uncouth brawler, or wield a sword like a mere infantryman. She casts her cards and lets them do the work for her. Even the weapon cards, superimposing the action of the card over Katia’s body, stresses that it is the monster, not the princess, who does the violence.

To put it another way, they are her subjects. She gives them orders. Katia herself remains unsullied, unspoiled. Distant.

This is, at least by my reckoning, a very different take on a female video-game protagonist. There’s something comparable with Link from the Zelda games, insofar as Katia is silent, distant, and often inexpressive, but she also lacks Link’s direct involvement in violence. Where video game heroines often arrogate the masculine-associated act of violence to themselves by taking on typically masculine traits, Katia retains her feminine characteristics, and only participates in violence at a remove. I’m not sure what the feminist reading of this might be (Does she more fully express her femininity through non-violence? Or does this assume that violence is restricted from women?), but I am very interested in the power dynamic expressed by Katia and Helena (who use their runestones to protect their respective kingdoms) versus the male Enchanter (who uses his runestones to destroy and accumulate power). The game also strongly implied that Gurd (representing the god of harmony) is female, and the god of creation shows female traits as well, while the god of destruction is distinctly more masculine. (Maybe some Taoist undertones here?)

But it is also worth nothing that combat, frenetic as it may be, is always twice removed from the player: you control Katia from the distant vantage point of the camera, and she controls the cards. That’s not to say that the controls are unresponsive—in fact there’s a pretty sweet mechanic where you ignore damage taken if you time a card cast just right, making offense a viable defense as well (in true Dark Souls fashion)—but just that you are always at a serious remove from the action. It is fast, but not imminent; engaging, but not stressful. Between the bird’s eye view of the battlefield, the twice-removed actions, and the multiple enemies and allies, combat often feels as much like an RTS as an action-RPG.

Why so Distant?

Add it all up, and the distant tone seems to be consciously reinforced by a lot of the game’s choices. Katia retains her regal distance from her human and monstrous subjects; you retain your godlike distance from Katia. The game’s tragedies and plots are on display, but you are not encouraged to identify with Katia’s suffering, thanks to the indifferent music, inexpressive faces, and stilted motions.

Many critics read this as bland, or the product of technical limitations. And that is possible. I can’t argue with what they felt or experienced.

But what I experience is a myth. A fairy-tale. High fantasy, in Tolkien’s sense—where the characters are larger-than-life, heroic figures and the drama is always at a remove. When I play Lost Kingdoms, I play it like I read the myths of Homer, knowing full well that I am watching fate play out in front of me—a story told many times before, and to be told many times again. That arch, “generic” plot and the mish-mash of monsters all serves to drive home the “once upon a time”-ness of this fantastic world. Katia, to me, is like every good princess who must save her kingdom from an evil Enchanter using her wits, her confidence, and her royal bearing. And while the dangers are real, the threat of death grave, it is also mythic: it cannot, will not happen to her, because her stark heroism will continue to shine through the darkness.

To me, all of this works. I find the distant tone of the game as relaxing and familiar as re-reading a favorite book from my childhood. I don’t identify with Katia—not even as a power fantasy, very much—but (to paraphrase C. S. Lewis) I weep for her as I weep for all humankind. She is larger than life. Her story is larger than life. And her quest to set right a hostile, threatening, divided world is the same quest we are all on, all the time, even if our actions seem small and insignificant. We too must follow our parents only to lose them. We too must defeat our enemies only to discover that they were our allies. We too must seek help from the gods in order to overcome powers beyond our ken. And we too must learn to wield the power thrust upon us, even though we barely understand it or why it has been entrusted to us.

I think Lost Kingdoms succeeds at what it is trying to do (the occasional camera problem notwithstanding). But I think it failed to reach people because that wasn’t what they wanted from the game.

How a Video Game Fails

2002 was a very strange year in the history of video games. The PC gaming scene was at a strange nadir—adventure games were “dead”, World of Warcraft hadn’t yet revolutionized the way multiplayer games worked (though both Final Fantasy XI and Warcraft III came out this year), and the rich independent scene of the 2010s had yet to blossom. Consoles were riding high, but this was a transitional year for most: the year after the new generation had been released, before a standard had been set for the new hardware.

In some ways, I think it was a year ripe for experimentation. It was the year that Kingdom Hearts first released for PS2, and the year Morrowind came out for PC and Xbox; both of which were janky, experimental games that would go on to be the foundation for juggernaut franchises. Eternal Darkness: Sanity’s Requiem also released for the Gamecube, and remains a beloved off-beat title with a similar legacy of interesting, unique mechanics and disregard for the time’s conventions. Meanwhile, GTA: Vice City set a new bar for the powerhouse Grand Theft Auto franchise, released on PS2, Xbox, and PC, and remains a sort of high-water mark for the days when Rockstar Games made no pretensions to serious storytelling. And the GameCube saw one of its most successful years in the lifespan of the console: Metroid Prime, Super Mario Sunshine AND Zelda: Wind Waker (in Japan) all released this year, and remain the highest-regarded single player games in the console’s history, despite the legacy of Sunshine and Wind Waker being a little fraught compared to other releases in their respective franchises.

So what happened to Lost Kingdoms?

I think part of the reason Lost Kingdoms failed where Eternal Darkness succeeded is what we’ve discussed: the lack of polish endemic to its mechanical ambitiousness failed to distinguish it among super-polished games like Mario Sunshine and Wind Waker, and the understated, distant story failed to connect with gamers of the time (unlike Morrowind, which had unprecedented size and scope to balance its equally-understated story; or Eternal Darkness, which history remembers for its pulp-horror tone).

It was not a time for subtlety, in short. It was 2002. Vice City was game of the year and even Link was a cartoon. To get noticed in this market, you had to have all the gleam and polish of Mario Sunshine, all the theatricality of Eternal Darkness or Kingdom Hearts, or the visible ambition of Morrowind or GTA. The world was not ready for a game of quiet gloominess like Dark Souls, but without its fine-tuned combat mechanics.

But are we ready now?

I’m tempted to say yes: that part of the reason Lost Kingdoms failed was that it couldn’t live up to the competition. This was before the independent scene, before there was room for AA games with a certain tolerable amount of jank like Hellblade: Senua’s Sacrifice or Hand of Fate. I want to say that we’ve grown more discerning as a community, and can now respect the subtle storytelling of Dark Souls, tightly-constructed short games like Transistor, the mechanical ambition of…of…

Well that’s just it, isn’t it?

Much as I love the indie scene, the classic formula for a successful indie game is not “mechanical ambition” – it’s to find a fun mechanic and explore that one mechanic to its logical conclusion. Baba is You riffs on the mechanic of manipulating its own rules. The Witness has literally one kind of puzzle, iterated over and over again (though that’s more than a little over-simplified). Loop Hero, Slay the Spire, Superliminal, Return of the Obra Dinn: all explore their one mechanic in a streamlined, no-frills environment. Lost Kingdoms has a big, sprawling, messy mechanic, and doesn’t boil down to a tight, polished experience.

But there is one key component of modern gaming that Lost Kingdoms would certainly have benefited from: patch culture.

Now I’m not saying that patch culture or Early Access is necessarily a good thing. Lots of companies ship ugly, misshapen games out the door, charging $60 for what is essentially an unfinished product. But if there’s ever been a game that would have benefitted from everyone collectively looking the other way for a month or two while the development team figured out how to perfect its mechanics, it would be Lost Kingdoms. If Lost Kingdoms were released in Early Access, or if we gave it the benefit of the doubt we gave to No Man’s Sky, Skyrim, or Cyberpunk 2077, willing to redeem it back into the fold after a few months’ (or years’) worth of quality-of-life updates, I think we might have seen something truly special and memorable.

If anything killed Lost Kingdoms, it was the permanence of releasing games on console in 2002. There’s no going back from a bad release in 2002.

But, then again, we did get a rare second shot at it in this case.

Lost Kingdoms II: Bigger and Bulkier

On paper, Lost Kingdoms II is everything I could have wanted. More cards. More diverse mechanics. Direct interaction with the world, rather than only being able to use cards in instanced combat encounters. (Use cards to blast through obstacles, jump up cliffs, fly across chasms!)

But it also “fixes” all the “problems” of the first game. It takes considerably longer to beat, and encourages revisiting levels rather than locking them off after you play them (and you will have to, in order to unlock the best areas). There are post-endgame challenges with more cards to collect. There are more characters. More dialogue. More dynamic music. More upbeat sound effects and monster animations. Clear emotional stakes for the protagonist. Even a quasi-love interest!

And…it doesn’t work. The dialogue delivery is stilted and emotionless; the character animations remain stiff and uncomfortable, but now they are supposed to be human beings instead of faceless homunculi populating a wasted world. It was honestly better when you just had to read all the lines yourself in the silent, haunting void.

It’s not a complete loss, though. Many of the new cards are interesting and exciting (though I find I never play with the much-touted new machine cards). Sol, your escort-slash-love-interest is actually one of the best-executed companion characters I’ve ever seen, mechanically. There’s at least one level where your runestone has been taken away and he actually protects you, cutting down enemies with his sword while you run around trying to avoid them—it’s an evocative scene, reversing the usual video game escort quest, and makes your relationship to Sol that much more valuable and important. (Seriously: once again I want to point the collective attention of game developers to this game and say, “THIS. THIS is what good storytelling-by-way-of-mechanics looks like!”)

But that all-important tone has become, in actuality, as bland as the critics of the first game made it out to be. Gone is the consistent monster design. In and among the creepy and threatening monsters like the Zombie Dragon are monsters that are comically-inept, like the Sleeping Giant (who has a 50% chance of falling asleep when you summon him, rather than performing his attack), or the Hagans (who all have fart attacks), or CircaSaurus (who is apparently a lizard on a circus ball, reversing your controls while you maneuver him around the field). The levels are mostly well-lit and cheery, despite the protagonist, Tara, brooding and sulking her way through her childhood hangups.

And yet the actual story is freaking grim. The Kendarie army has been mass-producing runestones by (we discover) sacrificing human beings (including your merry band of thieves) to the god of harmony (now a huge monster; Gurd reluctantly admits the relation like it’s some black-sheep uncle we don’t talk about). But when the King of the Kendarie discovers that you (and not the queen) have the true runestone handed down by Queen Katia of the first game, he uses his army to lay waste to the kingdom of Alanjah. (including a positively devastating level where you walk through the ruins of a town destroyed by the army. At one point, a thirsty man asks you to find the mechanism that raises the water level so he can drink from the fountain. When you return, you find him dead. The Kendarie poisoned the well. Really dark stuff.)

When you arrive in the castle, the queen (your long-estranged twin sister; your mother abandoned you as a child to avoid a succession crisis) takes your runestone from you to defend the castle, only to fail miserably. You retrieve the stone and Sol escorts you from the castle, giving his life for you as he does (unless you fulfill the conditions for the “good ending”, which is very well hidden). Utterly alone, you follow the queen to their safehouse, where she gives you the key to unlock the god of destruction card, which you use to break into the castle, kill the Kendarie king, and destroy the god of harmony, who curses you with the threat of discord and war forevermore, but it’s OK because you and your sister (and Sol, if you saved him) live happily ever after. “It’s good to have friends again,” your flashback-self tells you.

It’s…weird. The actual events of the story are capital-D dark (though roughly on par with the first game), but the upbeat level design, music, monster design, and moral make it a tonal mess. Add in the wooden line delivery and the game is very unfocused. The gameplay is still rich, varied, and interesting, especially now that the game has several major endgame challenges (like the twenty-levels-deep Proving Grounds, where new, epic-level monsters and cards lie in wait for the brave—or foolhardy), but there’s also a really-annoying element-affinity system that doubles the cost of high-level cards until you’ve reached a certain affinity for that element—and yet every time you use a card, it lowers the affinity for the other elements, forcing you to grind affinity or suffer unexpected reversals in difficult combat situations. Also, there are gated treasures in virtually every level, forcing you to frequently revisit levels you’ve already beaten (though there are new things to find). So gone, too, is the knife-sharp grind-less pacing of the first game. Alas.

I still like Lost Kingdoms II, and don’t believe it deserved to be as thoroughly forgotten as it was. It’s an ungainly sequel, but still enjoys some positively inspired design decisions, and, along with its predecessor, remains unique in its mechanics and ambitious delivery. It, too, sits confidently on my shelf of Gamecube games, and has since it ambushed me from an Electronics Boutique bargain rack in 2004. (I nearly peed myself to discover that Lost Kingdoms had a sequel. I couldn’t buy it fast enough. And I regret nothing.)

The Non-Legacy of Lost Kingdoms

The first Lost Kingdoms won a Nintendo Power cover story and full review. Lost Kingdoms II got a cursory review in June 2003. It was completely upstaged by the even more spotty Gamecube releases of 2003: Splinter Cell, Enter the Matrix, and the American release of Wind Waker and Pokemon Ruby/Sapphire. There was no fanfare; no critical reception. It didn’t make a splash upon release. It didn’t become a cult classic. The lull of early 2002 broke to Lost Kingdoms’ advantage; Lost Kingdoms II couldn’t even exploit the greater lull of 2003. I would have missed it completely but for dumb luck—and I was exactly the person who wanted it most. Lost Kingdoms II was the make-or-break game for the franchise, and it didn’t even so much as flop as quietly get swept off-stage without anyone noticing.

But much as I want to share my love for this franchise, I’m not sure I will ever be successful. It’s not a perfect game. It doesn’t have the immediate appeal of other outré Gamecube titles like Eternal Darkness or Killer 7 or Viewtiful Joe. The first game is slow, thoughtful, and distant. The second is messy and clumsy. When the developers had a chance to perfect their vision for the first game, they instead made concessions to the critics and produced a committee-designed camel of a sequel.

But both are utterly unique. I’ve never played anything else like them. I can get my Zelda fix from any of a dozen games, but a Lost Kingdoms fix can only be had from these two games. And I imagine it will stay that way. I take a certain perverse pride in the fact that the games now sell for over one hundred dollars easily on ebay and Amazon—the mark of a game that didn’t sell many copies, but that is treasured by its fans nonetheless. There are a handful of fans who maintain online strategy guides and wikis for the games, but they don’t have nearly the presence of a one-off cult hit like Beyond Good and Evil or Eternal Darkness. Lost Kingdoms is, at least nowadays, niche of niche. You can track down the ROM pretty easily if you’re interested in playing it (I tend to think Lost Kingdoms well meets the scarcity/unprofitability-for-developer threshold for guiltless emulation). But I can’t imagine that will win many converts to my side. As the graphics and gameplay grow more and more dated, I imagine the game will become just that much more niche.

And I think I’m OK with that.

Lost Kingdoms is a game about being alone. About the world depending on you as you navigate a series of empty, gloomy environments. It’s about fulfilling the responsibility of your station: a responsibility that nobody else can share with you.

It’s fitting, then, that I bear this torch alone. That the light of the runestone burns on my back because only one can carry it at a time. We’ve all wielded the Master Sword, defeated Bowser, ridden the airship over Midgar or Spira. I alone have walked through the graveyard of Alanjieh’s great kings and overcome the Necromancer defiling them. I alone returned to Bhashea castle to find it overrun with avatars of Death and freed the Demon Swordsman from his prison. I alone tamed the White Tiger, overcame the trial of the Blue Dragon, saved the realm of the Golden Phoenix. I alone defeated the shade of Katia lurking in the Sacred Battle Arena and claimed her responsibility of rule.

One of the most powerful (and thought-provoking cards) of the two games is the Doppelganger. When summoned, it produces an independently-moving copy of your own avatar. The Doppelganger aimlessly strolls around the battlefield, seemingly harmless among the other enemies with their swords, claws, and aggression to the player. But when the Doppelganger encounters any being: friend or foe (including the player character), it immediately kills it and vanishes, warping out of existence.

The message is clear: you must play this game alone. Your allies and enemies are distinguished only by a temporary, fleeting loyalty. The difference between an enemy skeleton and one you control is determined only by the power you wield through your runestone. And by Lost Kingdoms II, only the one runestone remains. All the others are overpowered and absorbed by Katia’s march to conquer the gods.